The following is an edited transcript from the The Michael Knowles Show.

* * *

Scott Adams has died.

It is a sad story, though not an entirely unexpected one. And it’s important to note, Scott Adams did not kill himself.

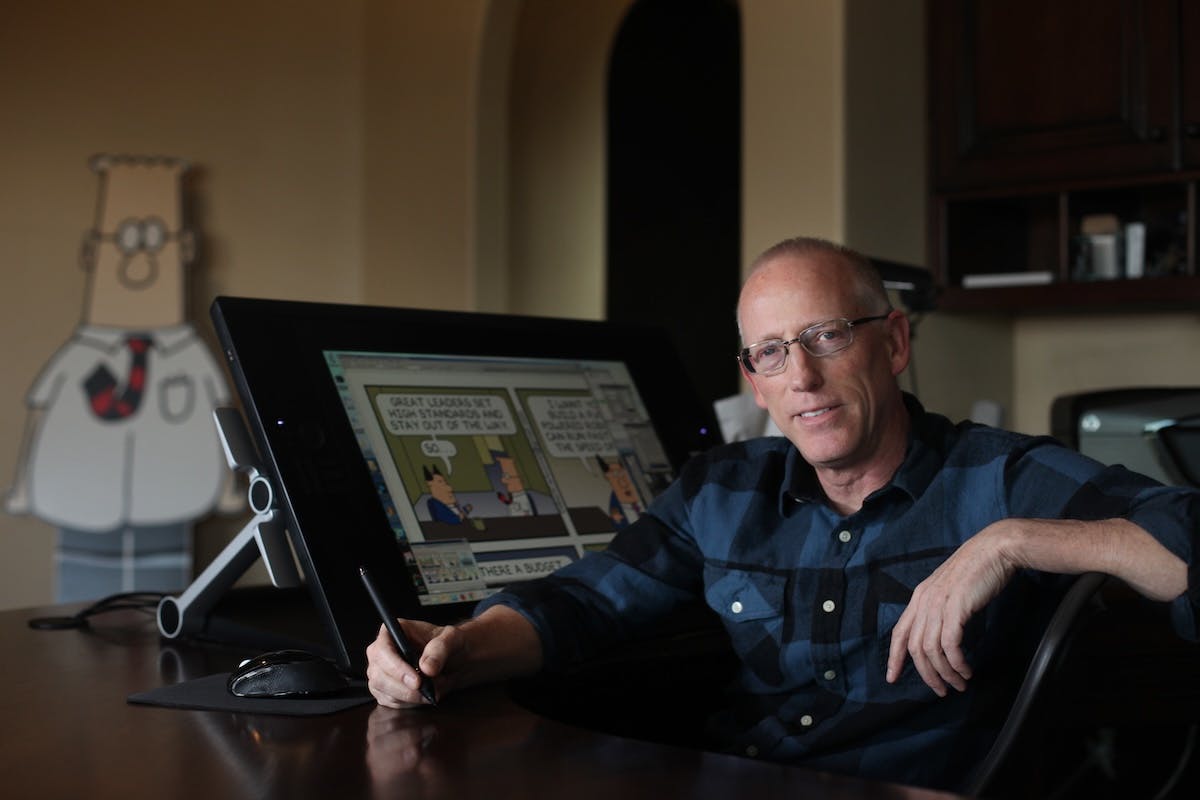

Adams, the cartoonist behind Dilbert, was a defining cultural figure for decades. His comic strip was a genuine phenomenon — so much so that, flipping through old Dilbert panels, one can feel a kind of nostalgia, like being at a parent’s house. He was a delightful figure in American public life.

Adams did not stop at cartoons. He parlayed his success into a second career as a writer and thinker on persuasion, self-help, and politics. He became one of the earliest and most incisive commentators to notice something many others missed about Donald Trump: that Trump was not simply a big dummy saying big dummy things, but an extremely persuasive communicator. Adams could articulate that insight with unusual precision, in much more expansive terms.

In recent years, however, Adams became associated with a much darker subject: assisted suicide.

And yet, Scott Adams did not kill himself. Despite living in California, where physician-assisted suicide is legal under certain conditions, Adams ultimately chose not to end his life that way.

But he very nearly did.

In public discussions and on his own show, Adams spoke candidly about having been declared terminally ill, having received certification from doctors, having completed the paperwork, and even having obtained the lethal drugs prescribed for assisted suicide. At one point, he admitted that he had internally planned to take his own life on a specific date. That moment came and went. Adams did not take the drugs.

Here he is back in June of 2025 talking about it:

Scott Adams Update: In May, he was in intense pain and didn’t expect to make it past today or tomorrow.

Now, his new cancer treatment has eliminated his pain and may extend his life by 1-2 years!⁰@scottadamssays So do I feel like I’m on borrowed time? Got a little extra?

Oh… pic.twitter.com/PWc2UR1pqN

— jay plemons (@jayplemons) June 29, 2025

Credit: @jayplemons/X.com

For years prior, Adams had been one of the most vocal defenders of assisted suicide in public life. After his father’s death in 2013 — a death Adams described as painful and prolonged — he sought to defend assisted suicide in Reason magazine, writing:

I’m okay with any citizen who opposes doctor assisted suicide on moral or practical reasons, but if you have acted on that thought, such as basing a vote on it, I would like you to die a slow, horrible death too.

The argument was blunt: opposition to assisted suicide was, in Adams’s view at the time, complicity in torture.

But something changed.

Only after Adams had committed to the process — after he had received the drugs and contemplated using them — did he realize it was more complicated. He begin to grasp what assisted suicide actually entailed. It was not, as it is often advertised, a clean or painless “going to sleep.” The process could involve vomiting, prolonged unconsciousness, and hours of dying while loved ones stood by, waiting, checking repeatedly to see whether the person was dead yet.

The act that had been sold as a mercy turned out to be something else entirely. Whatever pain the dying person sought to avoid would instead be imposed on family and friends. The poor family not only has to endure the scandal of watching a loved one kill himself, the very thing that is much more likely to persuade the loved ones around them to kill themselves. Suicide, after all, is not merely an individual act; it is a social contagion — it is long-documented as a contagion, especially among those who admire or identify with the person who chooses it.

Adams eventually summarized this realization while speaking to Dr. Drew Pinsky and Greg Gutfeld, saying, “It’s not as cool as I thought it would be.”

WATCH: The Michael Knowles Show

And there’s the irony of Scott Adams’s final chapter. A man who had spent years publicly advocating for assisted suicide ended his life by rejecting it. And in doing so, Scott Adams offered us one of the best examples of dying well. An amazing irony in the grand scope of Providence.

He was calm. He was loving. He did not hide it.

Today, we hide death. We institutionalize it. We rush through funerals and euphemize loss. We prefer not to look at dying at all. In earlier eras, particularly in the Middle Ages, a “good death” was understood as one in which a person knew death was coming, put their affairs in order, reconciled relationships, and prepared spiritually for what followed.

That is what Adams did.

We should pray for him. We should pray for his soul.

Though he was not a lifelong believer, Adams spoke openly near the end of his life about being persuaded by Pascal’s Wager and by his loving Christian friends. He did not pretend to believe. Instead, he adopted an attitude of humility that is almost shocking in its simplicity: I want to believe. I want to spend eternity with Jesus. If I wake up in heaven, that will convince me.

Some will quibble over the theology of those words. But there is something undeniably childlike about them — in the best sense. Not childish. Childlike. As Scripture reminds us, it is precisely this posture that Christ holds up as the model for entering the Kingdom of Heaven.

Adams could have scandalized the world. He could have taken his life and inspired others to do the same. Many people looked up to him as an “internet dad,” a guide through cultural and political chaos. His suicide would have rippled outward, causing real harm.

Instead, he chose restraint, honesty, and peace.

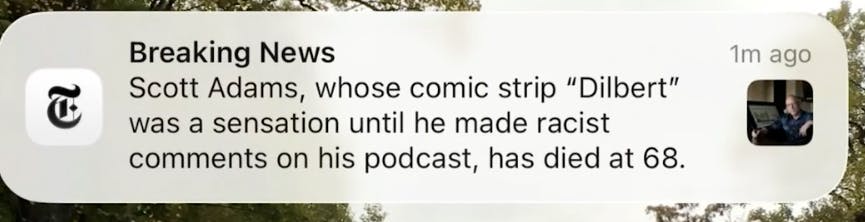

The reaction from the legacy media was, sadly, predictable. The New York Times and Boston Globe framed Adams’s death not with reflection or mercy, but with denunciation, labeling him racist even in death.

Here’s the breaking news alert from The New York Times:

Screenshot: iPhone

This is what they do. Listen, we’re talking about the political Left which celebrated the assassination of Charlie Kirk. So, yes, when a prominent Right winger dies, they’re going to find some way to attack him, even in his death. If they’re willing to do it to Charlie, they’re willing to do it to anybody. It’s sad, but they will celebrate your death.

Contrast this with how the Right generally responds to tragedy: even when acknowledging wrongdoing or responsibility, there remains sorrow. There is room for grief.

The New York Times wants to define Scott Adams by his worst comments. But I don’t think their narrative sums up his life at all. Then again, I don’t believe most of what I read in the New York Times.